The Legality of Russia’s Use of Naval Mines in the Black Sea

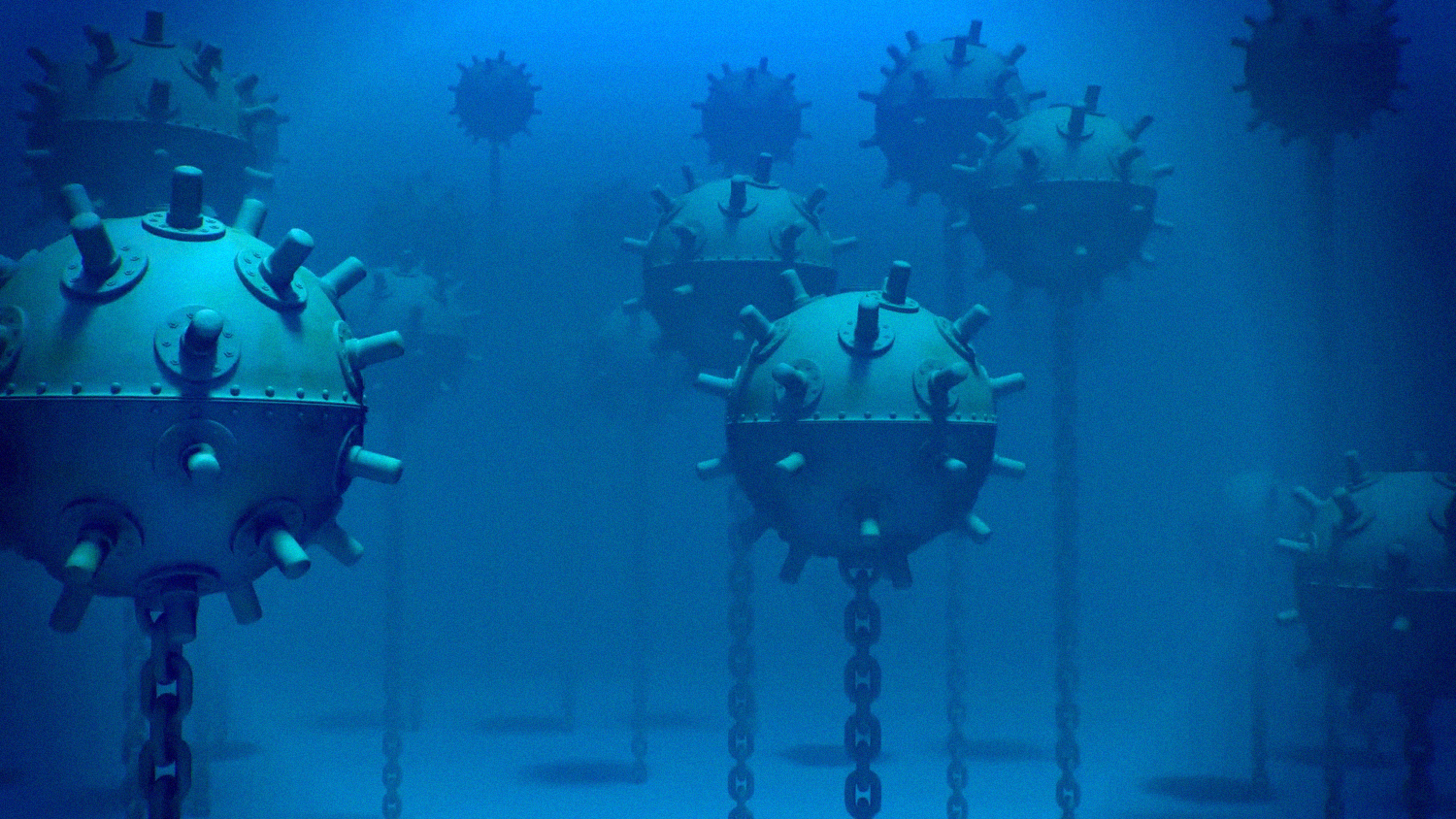

Naval mines have been a part of warfare for over a century, but their use is strictly regulated under international law to prevent harm to civilians and neutral ships. While not illegal per se (meaning that their existence is not illegal), naval mines can be dangerous, and rules are in place to control when and how they’re used. Recently, the spotlight has turned to Russia’s use of these weapons in the Black Sea during its war in Ukraine, raising serious questions about possible further Russian violations of international law.

The Hague Convention and Naval Mines

One of the key treaties that regulates the use of naval mines is the VIII Hague Convention of 1907. This treaty was established after the devastating loss of civilian lives from unchecked naval mining during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). The goal was to prevent similar tragedies by laying down clear rules about where and how naval mines can be used, especially to protect neutral ships.

According to the treaty, countries cannot scatter mines that may indiscriminately injure civilians and neutral vessels. For example, floating mines must deactivate within an hour if they’re no longer under control, and anchored mines must become harmless if they break free (Article 1). Moreover, states are prohibited from laying mines with the sole purpose of targeting commercial ships (Article 2). Any mines placed must be done with the safety of peaceful shipping in mind, and combatants need to inform others about the presence of mines in dangerous areas.

Even though not all countries signed this treaty, including Russia and Ukraine, many of its key points have become part of customary international law, meaning they apply to all nations, including Russia and Ukraine. This is where the issue of Russia’s actions comes into focus.

Customary International Law: Additional Protections

In addition to the Hague Convention, the use of naval mines is further restricted by legal principles that are part of customary international law. These include the principle of distinction and the right of innocent passage.

The principle of distinction, which is outlined in the 1949 Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols (Articles 48, 51(2), and 52(2) of Additional Protocol I), prohibits attacks that are directed at civilians or non-combatants. It requires that combatants must always differentiate between military and civilian targets. Indiscriminate attacks that fail to make this distinction are unlawful. This principle, recognized as customary international law, is one of the most fundamental rules in warfare. The International Court of Justice has highlighted that the principle of distinction is one of the “intransgressible principles” of international law (para. 79), and it has been integrated into military operational doctrine worldwide. Unfortunately, however, the UK government has observed that Russia has consistently violated this legal principle as they have “systematically targeted Ukrainian port and civilian infrastructure,” throughout its war.

The right of innocent passage, codified in Article 17 of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III), protects civilian ships passing through territorial waters, provided they do so in a way that does not threaten the peace or security of the coastal state. Russia ratified UNCLOS in 1997, meaning that it is bound by this principle. When naval mines disrupt the safe passage of these civilian vessels, it violates this right.

Both of these principles—distinction and innocent passage—have been cited in key legal judgments, such as in the U.S. v. Nicaragua (1984) case, and apply universally, further highlighting the legal obligations that Russia is infringing upon in its current mining practices.

Naval Mines in the Russia-Ukraine War

While the true extent of mining operations remains unknown, media and other reports indicate that Russia has deployed hundreds of naval mines in the Black Sea since its invasion of Ukraine in 2022. This includes floating mines, sea bottom mines, and anchored contact mines. Some mines floating in the Black Sea are anchored contact mines that have become unmoored in stormy weather. Reports note that mines have been dropped “in the direction of navigation corridors of civil shipping,” including in a “humanitarian corridor” established by Ukraine in the western Black Sea safeguarding the export of grain to Europe and Africa. Shipping vessels have been hit by these mines near Ukraine’s ports and some mines are reportedly floating near Turkey, Bulgaria, and Romania.

The UK Foreign Office indicated that Russia has “almost certainly” laid these mines as a covert attempt to lay blame on Ukraine for attacks against civilian vessels, rather than openly sink civilian ships. These mines have threatened significant disruptions in commercial shipping in the region, including with respect to the export of Ukrainian grain, and tourists bound for Black Sea resorts have been deterred by such reports of drifting rogue mines. Around the same time, Russia also notably backed out of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, a deal brokered between Russia and Ukraine by the United Nations and Turkey meant to facilitate the safe navigation and export of Ukrainian grain and other foodstuffs via the Black Sea.

Legal Violations: Where Russia Crosses the Line

Russia’s use of naval mines in the Black Sea raises significant questions about compliance with international law. First, the types of mines being used are concerning. Under the VIII Hague Convention, floating mines are supposed to deactivate shortly after being deployed, and anchored mines should become harmless if they break free. However, reports suggest that Russian mines are drifting long distances and remaining dangerous well after deployment, potentially posing risks to neutral and civilian vessels.

In addition to the concerns about the types of mines used, a more pressing issue is the mining of the humanitarian corridor, specifically set up for the safe passage of cargo ships. This corridor is intended to be neutral ground, allowing civilian vessels to navigate without fear of attack or damage. By placing mines in this area, Russia may be violating international laws that are designed to protect neutral shipping.

To ensure the safety of neutral shipping, precautions should be taken, such as warning ships about the presence of mines or avoiding mining areas designated for innocent passage. While Russia issued a general warning about mines in shipping routes in July 2023, this notice has been viewed as insufficient. The Russian Defense Ministry referred to a single mine sighting without providing detailed information about the numerous mines laid in the area, which would be critically important information to seafarers.

Following the suspension of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, Russia has indicated intentions to target vessels entering or leaving Ukrainian ports and has carried out several strikes on the port of Odesa, disrupting commercial shipping in the region. Todor Tagarev, Bulgaria’s Minister of Defense and member of a new trilateral Mine Countermeasures Black Sea task force noted, “Russia has been blocking maritime traffic for many months now,” highlighting that “there are a number of sea mines that present risks… along with threats from Russian UAV and missile attacks.”

Moreover, as discussed above Russia may be infringing upon two important legal principles under customary international law: the principle of distinction and the right of innocent passage.

Can Russia Be Held Accountable?

So, what can be done about these violations?

International law provides mechanisms for accountability. States affected by Russia’s mines, such as Ukraine, Turkey, Romania, and Bulgaria, could bring a case against Russia before the International Court of Justice. The International Court of Justice can hear disputes between states and potentially order Russia to stop these activities or pay damages for any harm caused.

On the other hand, Russia might try to defend its actions by arguing that it did not intend to specifically target commercial shipping or that it is not bound by the VIII Hague Convention because it is not a signatory. However, many of the treaty’s rules have become part of customary international law, meaning that Russia is still expected to follow them. Additionally, intent is only relevant in certain cases, and the widespread damage caused by these mines may be enough to establish liability regardless of Russia’s motives.

Conclusion

Russia’s use of naval mines in the Black Sea is not just a military strategy—it has real-world consequences for civilian lives and international shipping. By mining the humanitarian corridor created to facilitate the safe navigation of civilian cargo ships, as well as by allowing its mines to drift far beyond their intended areas, Russia appears to be creating risks for commercial vessels and civilians in Ukraine’s territorial waters. As such, Russia’s actions in the Black Sea humanitarian corridor does not align with key doctrines of international law, jeopardizing civilian safety and challenging the integrity of international legal frameworks designed to uphold peace and security.

As the conflict continues Russia continues to violate international law. However, the international community will be watching closely to see how these actions are addressed, and whether Russia will be held accountable for its violations of international law.

Authors: Dr. Gregory P. Noone and Sindija Beta, PILPG, and Danek Freeman, Joon Cho, Joseph Hahn, and Leigh Dannhauser, Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP

Conceptualizing IHL is a series of essays on various topics of international law limiting the use of violence in armed conflicts. These laws are grounded in the fundamental need to protect human dignity and alleviate civilian suffering during times of war

This material has been developed by the Public International Law & Policy Group for the Center for Civil Liberties. The materials of this series are allowed to be published on other resources in whole or in part, provided that the authorship is indicated and an active hyperlink to the organization’s website is provided. This text does not express the position of the Center for Civil Liberties, but solely that of the author(s) of the blog.