The forcible transfer of Ukrainian children as cultural genocide: Challenges and alternatives for prosecution and punishment

Introduction: The elusive crime of crimes

Genocide is known the world over as “the crime of crimes”. Yet, for all its significance in contemporary international law and politics, its track record of prosecutions at international criminal courts is surprisingly scant, its conviction rate even lower. Although it was coined by Raphael Lemkin already in 1943, the term “genocide” did not make it as a discrete criminal offense in the Statute of the International Military Tribunal – barely mentioned during the hearings at Nuremberg thanks to Lemkin’s relentless efforts to raise awareness – and its nomen iuris would only enter the canon of international law in 1946 through UN General Assembly Resolution No 46(I), eventually crystalized as a full-fledged legal concept with the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

Although the ad-hoc international criminal tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda set up in the 1990s contributed greatly to the punishment of this crime, the only permanent international criminal tribunal in the world today, the International Criminal Court, has only charged one individual with the crime of crimes for actions committed in Sudan. To this day, Omar Al Bashir remains at large and no conviction has been handed down by the ICC on that or any other particular case of genocide.

Consequently, it has come down to domestic criminal courts to make sure the crime of crimes is adequately prosecuted and punished as mass atrocities are woefully still a part of the political landscape of the 21st century. For example, Germany has recently convicted former ISIS fighters for the crime of genocide perpetrated against Yazidi minorities in Iraq and Syria.

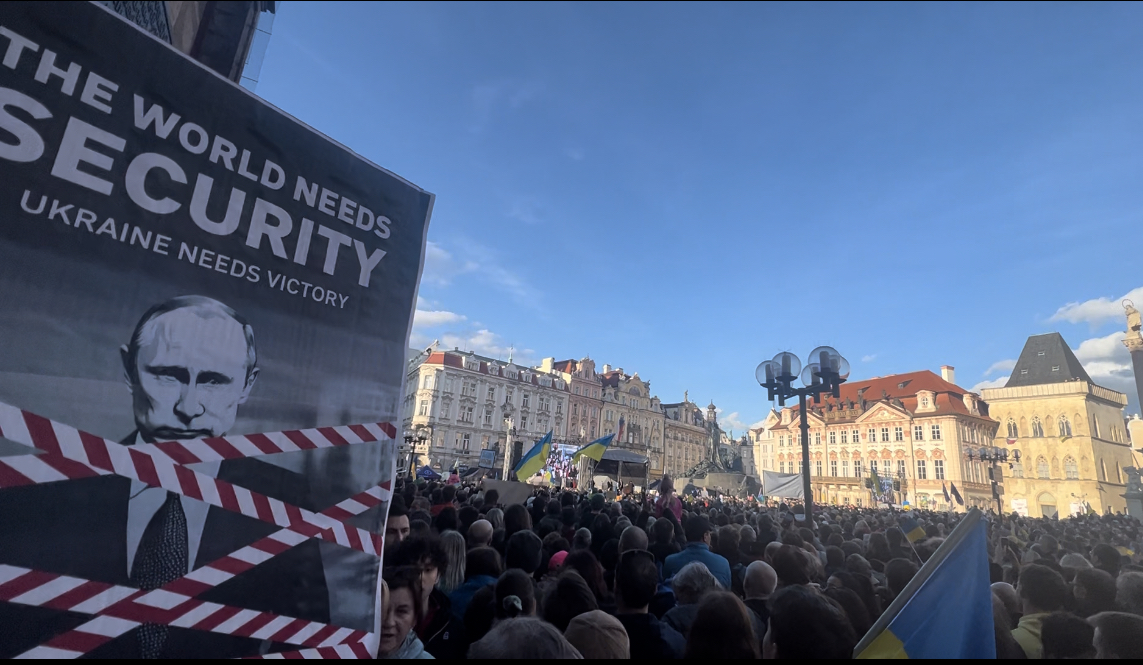

Another case in point is Ukraine, where courts have issued criminal convictions against Russian nationals for war crimes and genocide committed against the Ukrainian people since February of 2022. Although there are international initiatives in place to support the Ukrainian legal system – including at the ICC, in the European Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States – the fact remains that Ukraine is the one spearheading the “legal battle” to prosecute genocide committed against its own population.

Cultural genocide: Killing the Ukrainian within

Admittedly, the war in Ukraine has laid bare the elusive nature of the crime of genocide in terms of its effective prosecution and punishment, as evinced by the decision of the Office of the Prosecutor of the ICC to charge Vladimir Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova, not with the crime of crimes, but with the war crimes of unlawful deportation of population (children) and of unlawful transfer of population (children) from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation.

Why not charge them also with genocide? Under Article 6 of the Rome Statute, which reproduces verbatim the legal definition contained in Article II of the 1948 Genocide Convention, the forcible transfer of children of a national, ethnical, racial or religious group to another group qualifies as genocide when committed with the required specific criminal intent – a dolus specialis that is notoriously difficult to prove.

The forcible transfer of children committed with genocidal intent is what is known as “cultural genocide”, that is, a conduct aimed at the destruction of the group not by means of the physical elimination of individual members therefrom, but by obliterating the cultural identity of said group, such that, for instance, an imperial power may “Kill the Indian [or the Ukrainian] in him, and save the man”. As Lemkin already noted in 1943:

“[g]enocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be the disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups” (emphasis added).

Accordingly, the Draft Convention on the Crime of Genocide prepared by the UN Secretary General in 1947 devotes a specific section to cultural genocide, understood therein as consisting “not in the destruction of members of a group nor in restrictions on birth, but in the destruction by brutal means of the specific characteristics of a group. (…) It [is] a policy which by drastic methods [aims] at the rapid and complete disappearance of the cultural, moral and religious life of a group of human beings”. It goes on to say that “The separation of children from their parents results in forcing upon the former at an impressionable and receptive age a culture and mentality different from their parents’. This process tends to bring about the disappearance of the group as a cultural unit in a relatively short time”.

As pointed out by Werle and Jeßberger, the forcible transfer of children is the only specific form of cultural genocide that made it to the final text of the 1948 Convention, under letter (e) of Article II therein, which reads: “Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group”. And although the ICC eventually decided to charge Putin and his subordinate with a germane war crime, the truth is that the forcible transfer of Ukrainian children to the Russian Federation has been extensively qualified as an act of genocide. Indeed, as early as 14 April 2022, the Rada (the Ukrainian legislative body), in full use of its constitutional powers, legally qualified said forcible transfer of children by the Russian Federation, among other conducts, as an act of genocide committed against a national group, the Ukrainian people.

In addition to Russia’s eliminationist rhetoric which is a matter of record, the abduction of Ukrainian children has been thoroughly documented by different reports, including one on the so-called “University Sessions” Russian program aimed at erasing the cultural identity of Ukrainian teenagers, as well in consecutive reports issued by the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine. As the head of the War Crimes Department at the Prosecutor’s General Office of Ukraine has remarked: “They want our children to leave, forget our language, history, culture, parents and grow up Russians. This is a typical example of genocide”.

And yet, despite all the strong indications that the crime of (at least) cultural genocide is being perpetrated against the Ukrainian people, it has come down to Ukrainian national courts to prosecute the crime of crimes, while the ICC has gone down a more cautious road relying on a less difficult to prove core crime, namely war crimes. It would appear that the almost unsurmountable obstacle of proving the specific criminal intent or dolus specialis required in the crime of genocide has effectively rendered Article 6 of the Rome Statute dead letter.

‘Dolus specialis incredibilis’: Doctrinal skepticism

Furthermore, even the author of the monograph famously dedicated to the crime of crimes, William Schabas, has shown strong reservations and even skepticism about the possibility to prove genocidal intent in the case of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In an article published in October of 2022, titled “Genocide and Ukraine: Do Words Mean What We Choose Them to Mean?”, Schabas decries the politization of the nomen iuris “genocide” by all parties involved. He also faces the challenge of cultural genocide head on, concluding that it cannot be prosecuted in the case of the war in Ukraine because, supposedly, cultural genocide “has been clearly excluded from the scope of Article II of the Genocide Convention by the case law of the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, and by the work of the International Law Commission”. Drawing on said authorities, Schabas argues that genocide must always consist of the physical or biological destruction of the group.

However, none of the authorities cited by Schabas actually refer to the forcible transfer of children. One of them, Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro), Judgment, ICJ Reports (2007) 43, § 344, bears exclusively on letter (c) of Article II of the Genocide Convention (“Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part”), hence its focus on “physical destruction” as per the literal wording of said literal. The other two, Judgment, Krstic´ (IT-98-33-T), Trial Chamber, 2 August 2001, § 580, and Report of the International Law Commission on the work of its Forty-eighth Session, 6 May-26 July1996, vol. II, Part Two, at 45–46, § 12, refer to cultural genocide more widely in order to dismiss its legal operability, without entering into details as to any sub-forms of commission thereof, such as the forcible transfer of children. In this specific case, Schabas confidently argues: “the textbooks require that for the transfer of children to amount to genocide there must be evidence of the specific intent to destroy the group physically”. However, the opinions cited by Schabas to support this claim, namely the aforementioned Bosnia v. Serbia case (§§ 344, 423, 438) and Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Croatia v. Serbia), Judgment, ICJ Reports (2015) 3, §§ 137, 390, again,only refer to cultural genocide in general and do not address the specific form of cultural genocide consisting in the forcible transfer of children, so it is difficult to ascertain where exactly said “textbooks” set out such a strict requirement.

Schabas analysis is, thus, at the very least incomplete as he does not clarify that the ICJ is only referring to letter (c) and not to the transfer of children; and at worst inaccurate as he reproduces the incorrect opinion of the ICTY in Krstic´ (stating that “despite recent developments, customary international law limits the definition of genocide to those acts seeking the physical or biological destruction of all or part of the group”) and of the ILC (which inexplicably classifies the transfer of children as a form of “biological genocide”) as they both wrongly state that the Genocide Convention supposedly excludes cultural genocide in toto, when it is accepted that letter (e) corresponds to exactly that particular form of genocide, admittedly circumscribed to the concrete modality of forcible transfer of children, thus excluding less tangible attacks on language, history and culture. As Werle and Jeßberger clarify: “Cultural genocide as such was not adopted into the Genocide Convention, nor is it recognized as a crime under customary international law; but the forcible transfer of children to another group, a specific form of cultural genocide, did become part of the definition of the crime” (emphasis added).

Alternatives: ‘A genocide by any other name’

The main challenge when it comes to the prosecution and punishment of the crime of crimes is, of course, proving the specific intent to destroy a group in whole or in part. Some Ukrainian legal experts, replying to Schabas’ skepticism, have recently made the case for the use of historical and political context in order to infer the required genocidal intent, bearing in mind that the current standard under international criminal law is that this must be the only reasonable inference available. For this, these Ukrainian experts rely on case law from the ICTY (Judgment, Karadzic (IT-95-5/18-T), Trial Chamber, 24 March 2016,§ 550) and the ICJ (the same Croatia v. Serbia case cited by Schabas). The former indicates that genocidal intent may be inferred from “the general context, the scale of atrocities, the systematic targeting of victims on account of their membership in a particular group, the repetition of destructive and discriminatory acts, or the existence of a plan or policy”. The latter points out that the characterization of all the forms of genocide and their mutual relationship “can contribute to an inference of intent”.

However, if inferring intent for such a stringent dolus specialis crime as genocide proves too difficult and threatens to thwart the effective punishment of harmful conducts altogether due to lack of evidence of genocidal intent, an alternative might be found in the prosecution of these conducts as war crimes under Ukrainian criminal law, which, unlike the Rome Statute, offers an pathway to both prosecute war crimes while at the same time recognizing the existence (and therefore the gravity) of genocide. As Shakespeare once wrote “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet”, and in that sense a genocide by any other name would smell as rotten and would still be in need of legal redress.

Genocide is a criminal offense in its own right under Article 442 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. Additionally, Article 438 therein codifies the crime of “Violation of the rules of warfare”, otherwise known as war crimes. War crimes are further defined and developed under Order No 164 issued in 2017 by the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense. Title I, Section 8 therein expands upon “Liability for violations of IHL”, which constitute war crimes pursuant to paragraph 4 therein. Paragraph 5 then lists what the serious violations of IHL directed against people are, including the discrete criminal offense of “inhuman treatment accompanied by degradation of human dignity, including the use of apartheid, genocide and other actions based on racial discrimination” (emphasis added). Since this is a war crime, the dolus specialis of genocide does not need to be proved in order to punish this conduct, as genocide is included in this context merely as an example of the means of commission of this particular war crime, not as a separate criminal offense for prosecutorial purposes. Thus, it suffices to prove the criminal intent behind the war crime itself.

According to the ICRC, the war crime of inhuman treatment amounts to the infliction of severe physical or mental pain or suffering. Under paragraph 5 of Order No 164, such pain or suffering must be accompanied by degradation of human dignity. Although the ICTY has defined inhuman treatment as either the infliction of serious mental harm or physical suffering or injury or as an act that constitutes a serious attack on human dignity (Kordić and Čerkez case, Judgment, Vol. II, Ch. 32, § 1330), Order No 164 clearly separates both and treats degradations of human dignity not as a reformulation of the core conduct but as an aggravating circumstance thereof.

Additionally, Order No 164 lists forms of commission of this war crime of inhuman treatment, all of which are based on racial discrimination as the last sentence indicates, including genocide (again, as way to commit this war crime, not as a separate crime). The motivation behind this particular war crime of inhuman treatment, therefore, must be racial discrimination. This is an example of a criminal category that incorporates motive alongside intent as part of the legal description of the conduct. In that sense, this particular war crime of inhuman treatment resembles genocide, as the motivation (i.e. the destructive aim or objective) is arguably also incorporated in this last legal category (as evinced by the words “as such” from the chapeau of the 1948 definition). However, it differs from genocide in that the latter is a crime that requires a “surplus of intent” or a “transcending internal tendency” (“überschießende Innentendenz”), which is not required for the war crime of inhuman treatment under Ukrainian law. All that needs to be proved is the criminal intent generally applicable to all war crimes.

Thus, in the case of this particular war crime defined in Order No 164, no genocidal intent needs to be proved as such, even though genocide is used as an example of a form of commission in the description of the criminalized conduct. This kind of amalgamation is not something unheard of in international criminal law. For example, the crime against humanity of persecution defined in Art. 7(1)(h) of the Rome Statute requires for the conduct to be committed “in connection with any act referred to in this paragraph or any crime within the jurisdiction of the Court”. The Elements of Crimes clarify that “It is understood that no additional mental element is necessary for this element other than that inherent in element 6”, i.e. the specific criminal intent required for crimes against humanity, namely knowing that the conduct was part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population. This way, genocide may be used there to adjuvate in the prosecution of another international crime (the crime against humanity of persecution) without need to prove genocidal intent, in a similar way that genocide may be used to evidence the commission of a particular war crime (inhuman treatment) under Ukrainian law without the need to prove that the specific war crime was committed with the intent to destroy a group in whole or in part.

Conclusion: ‘Which is to be master?’

Schabas ends his study of the (im)possibility to prosecute genocide in the context of the war in Ukraine with the following remark:

“When politicians and legislatures use the term ‘genocide’ without precise reference to a legal provision there can be no certainty as to what they mean. We are reminded of Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass. ‘When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less’, said Humpty Dumpty. ‘The question is whether you can make words mean so many different things’, replies Alice. International lawyers have no monopoly on use of the word ‘genocide’ any more than criminal lawyers have ownership of terms like murder, torture and rape. Nor do international lawyers necessarily agree on the meaning and interpretation of the term. However, case law of the International Court of Justice and the international criminal tribunals has become consolidated in recent decades around a rather restrictive approach to the definition”.

Schabas is right that we need more precision when we discuss legal terms such as genocide. But what we should ask ourselves is what do we need such precision for. Schabas leaves out Humpty Dumpty’s final retort to Alice in that exchange: “‘The question is’, said Humpty Dumpty, ‘Which is to be master – that’s all’”.

In that sense, we may ask whether we want precision only to be masters of a conversation, for instance, to readily point out when people use a word like “genocide” wrongly from a legal point of view; or if we are truly concerned with the best possible interpretation and application of legal categories that we all agree exist for an important reason and should be used when it is called for, that we may protect the legal interests underlying criminal law in a way that is both socially satisfactory and respectful of the principle of legality.

By drawing on existing Ukrainian criminal law, the almost insurmountable obstacle of proving genocidal intent in a war that, however, may be politically labeled as genocidal can be overcome by relying on alternative legal categories, such as war crimes, especially if they incorporate genocide as part of the description of the punishable conduct. Thus, by finding solutions that already exist in domestic and international criminal law, we may ensure that the interests underpinning our legal institutions are effectively safeguarded, such that words remain tools at our disposal instead of becoming the masters of our own experience.

Author: Francisco Lobo is a Doctoral Researcher at the Department of War Studies, King’s College London. He holds an LLM in International Legal Studies from NYU and an LLM in International Law and an LLB from the University of Chile. He has worked as a legal practitioner in the private and public sectors, and as a lecturer of international law and legal philosophy. His research focuses on international law, human rights, the laws and ethics of war, legal theory and moral philosophy