Segregation in literature: From Jim Crow to Apartheid

“Separate but equal”: in 1896, it was a convenient myth used to justify Jim Crow laws. Nowadays, the phrase is a reminder of the legal fiction underpinning segregation after the American Civil War. Decades later, South Africa instituted a similar system. Originally Afrikaans, ‘apartheid’ literally translates to ‘separateness’, relaying the core principle behind the regime. In both societies, segregation was violently imposed upon communities – generations later, the consequences are still apparent.

Today, we tend to divide people in such regimes into two categories: the oppressors and the oppressed, flattening a troubling reality. These systems contained a multitude of actors, with varying degrees of complicity. They persisted because of violence and propaganda, extracting compliance from everyone. The precarity of the ‘order’ imposed is evident from contemporary literature.

“Now my eyes are open and I can never close them again.” J.M Coetzee’s narrator in Age of Iron states this after she sees five boys lying in a burnt shed, murdered by South African State officials. Mrs. Currens’ realization comes at an odd point in the novel – a mere ninety pages from the end. Up until this point, the apartheid regime occupies a shadowy place in the narrative, resting in subtle allusions to poverty, the truancy of black schoolboys, and a daughter’s refusal to return to South Africa. The violent reality of the system only bursts onto the page when the narrator is forced to face its effects. From this point, Mrs. Currens is unable to ignore the role apartheid has played in her surroundings: “…when I walk upon this land, this South Africa, I have a gathering feeling of walking upon black faces”, reading the brutality of the system into the very land. To modern readers, this seems like a rather belated realization. When we think of pre-1990 South Africa now, it is a land defined by segregation and the subjugation of black people – any other view seems impossible.

However, the strength of Coetzee’s narrative lies precisely in its elision of such bold-faced assertions. Mrs. Currens is neither ignorant nor a racist. She is an old white woman, dying of cancer; an apt narrator for a novel set in late apartheid South Africa. She rages against those in power, saying they have spoiled her life the way “a rat or a cockroach spoils food without even eating it”. Despite Mrs. Currens’ supposed distance from the cruelty inflicted by white supremacy, her life is irrevocably ‘spoiled’ by association. Her comfortable existence in such a regime reflects the far-reaching depravity of the system, deepening an obsessive concern with her own mortality.

Mrs. Currens’ portrayal in Age of Iron attests to the precarious nature of segregation. On one hand, she lives her life in relative safety in 1980s South Africa, a stability only made possible by her whiteness. On the other, she admits she cannot be indifferent to the ‘war’ – “it lives inside me and I live inside it”. Her experience poses a difficult question for those who indirectly benefit from segregation systems: when does co-existence become complicity?

Ironically, Age of Iron came out in September 1990, mere months after apartheid officially ended. Amid a society mired in questions of transition, Coetzee’s narrative pushed readers to look back at the (very recent) past and reflect on their own role in history. Given the trajectory of other apartheid regimes, such reflection seems to be a crucial part of moving forward.

Harper Lee’s lesser-known second novel, Go Set a Watchman, was originally an early draft of the celebrated To Kill a Mockingbird. Written in 1957, the story concerns a 26-year old Jean Louise returning to Maycomb, Alabama shortly after Brown v. Board of Education outlawed segregation in public schools across the U.S. The landmark decision was followed by various laws addressing other aspects of segregation, eventually leading to the end of Jim Crow. The central conflict of the novel is Jean-Louise’s struggle with the racism she sees around her; she is unable to comprehend how “everything she learned about human decency” came from a place that seems so bigoted now.

The demand for equality, effected through a Supreme Court order, turns Maycomb on its head. People claim the decision sets a dangerous precedent, spelling the end of States’ rights. Others oppose the supposed speed of the overturning, claiming citizenship rights must be ‘earned’, and the local black communities “are still in their childhood as a people”. These arguments are unthinkably offensive now, but in portraying them, Lee’s narrative shows how the ‘end’ of such regimes is rarely accompanied with immediate amends.

Indeed, Maycomb seems more divided than ever. Jean-Louise’s aunt openly says that white people no longer interact with black people: “…after the thanks they’ve given us for looking after ‘em, nobody in Maycomb feels much inclined to help ‘em”. They read the black community’s demands as “insolence”, unable to accept a new power structure.

Jean-Louise feels the fracture deeply when she goes to see Calpurnia, the maid who raised her. Calpurnia receives her with politeness, not warmth; when Jean-Louise asks why, Calpurnia simply asks “What are you doing to us?”, subsuming their relationship into the reality of race relations. The newfound distance between them makes Jean-Louise reconsider her childhood: “…I swear she loved us…she didn’t see me, she saw white folks. She raised me, and she doesn’t care.” Ironically, the breakdown of Jim Crow is what makes race visible to Jean-Louise; earlier, her relationship with Calpurnia was defined by affection – now, she cannot escape her association with ‘white folks’. In this, Lee’s narrative strikes a deeper truth: segregated society warps relationships, masking foundational injustices. When it disappears, any illusion of harmony is impossible.

In To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus Finch was a champion of equality, defending a black man against impossible odds. In Go Set a Watchman, his views on integration seem dated and patronizing. Many readers found the shift jarring and yet, perhaps Lee’s earlier draft asks a more important question: what comes after segregation is gone?

It is still a tough question to answer. Given race relations in the U.S and South Africa today, the consequences of segregation clearly persist. Issues like police brutality, poverty, and health are divided along racial lines, and any past gains in reconciliation have faded in the face of present inequalities. Moreover, similar separationist thinking abounds all over the world, isolating people based on race, religion, and even language.

At first, reading about late apartheid South Africa or post Jim Crow Alabama feels foreign; in terms of time, these societies disappeared decades ago. However, these novels serve as an important reminder of what it actually means to systemically deny people their humanity. Unfortunately, they are deeply relevant today.

Author: Anuja Jaiswal, LLM, Transnational Crime and Justice, United Nations Interregional Crime and Research Institute

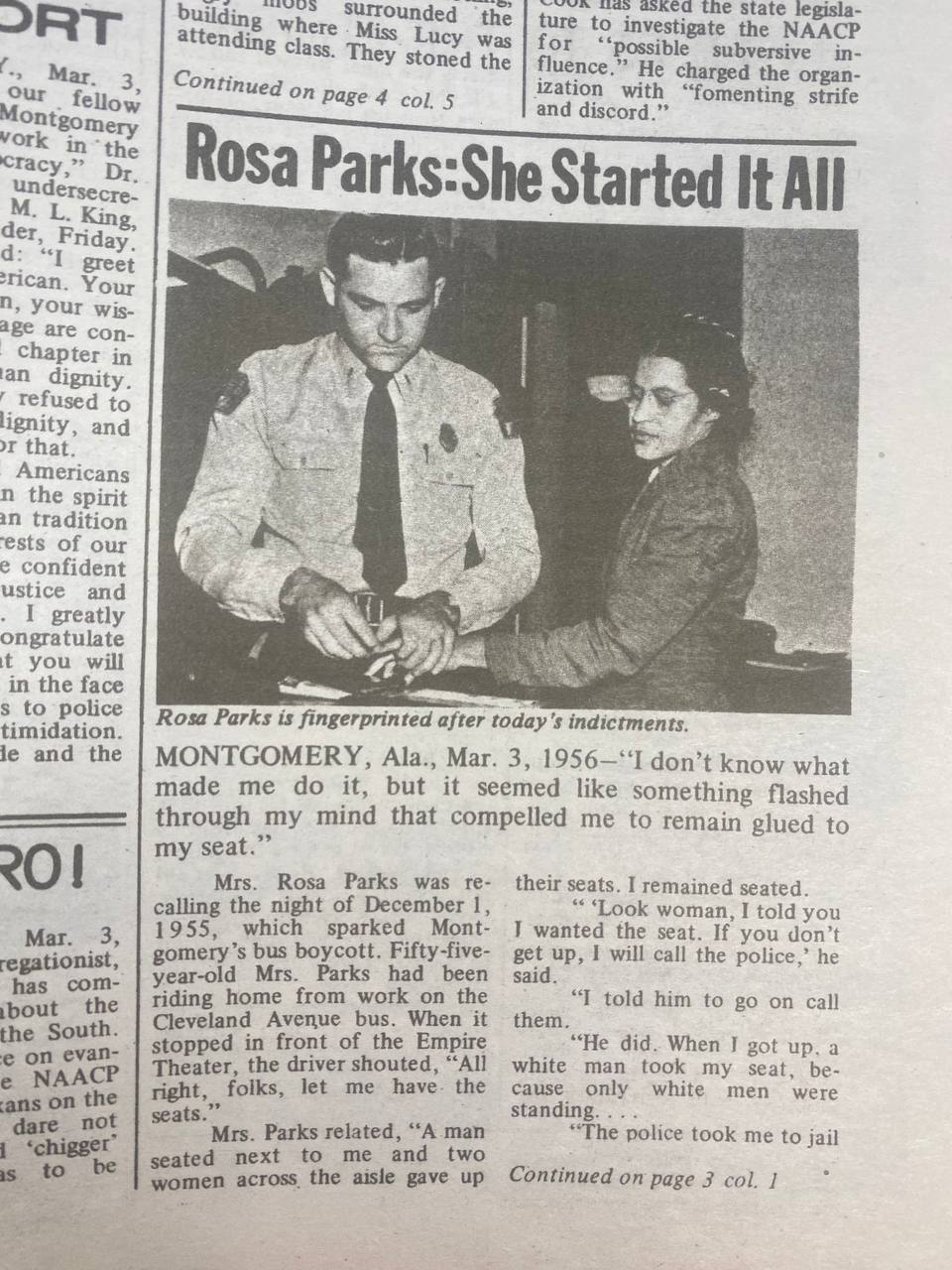

Photo: The Black Chronicle book is a compilation of 178 years of Black history from over 400 authentic news articles sequenced in a newspaper format. This insightful book is original, documented Black history at its best. Educators, public officials, professionals, students, and persons of all ethnic backgrounds are embracing and reading what is fast becoming a much sought-after international treatise consisting of reference work on Black history. Every home and every person across the nation should have a copy of this book. A must-read for all who want to know America’s full and complete history.