Why Ukraine Shouldn’t Wait for Its Own Nuremberg: Key Takeaways from the Public Discussion and Book Presentation

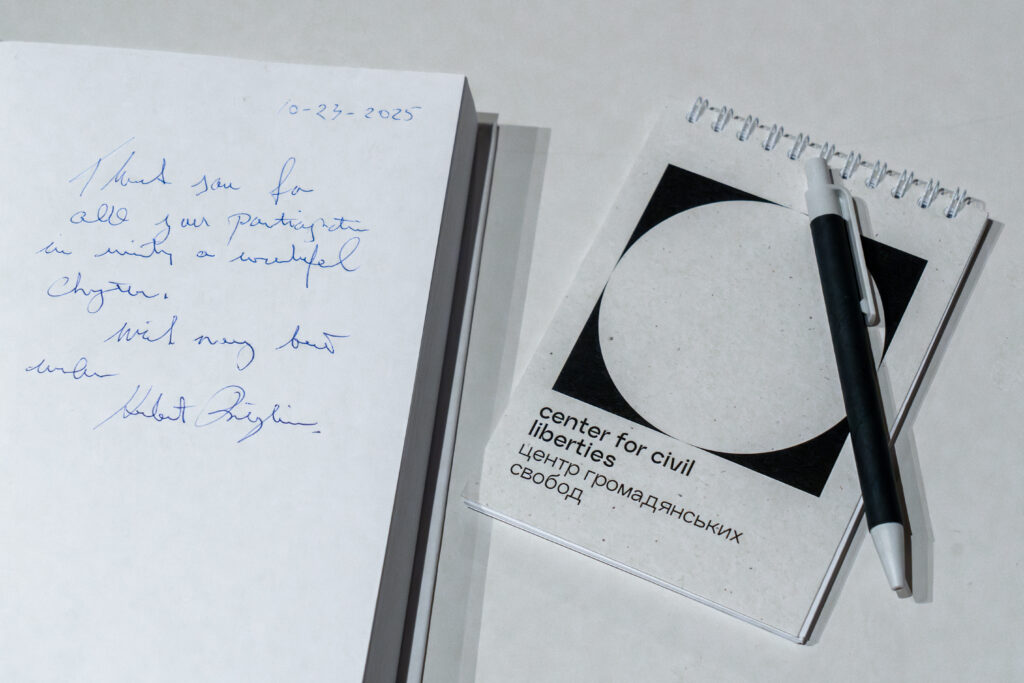

On October 23, a public discussion titled “Why Ukraine Shouldn’t Wait for Its Own Nuremberg?” took place, organized by the Center for Civil Liberties in cooperation with the SENS Bookstore.

The discussion accompanied the presentation of the book Nuremberg Principles and Ukraine: The Contemporary Challenges to Peace, Security and Justice.

The event brought together Herbert R. Reginbogin, Research Fellow at the Institute of Political Science and Catholic Studies, The Catholic University of America (Washington, D.C.); Anton Korynevych, Director of the Department of International Law at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine and Agent of Ukraine before the International Court of Justice; and Oleksandra Romantsova, Executive Director of the Center for Civil Liberties.

The discussion focused on how the legacy of the Nuremberg Tribunal can help Ukraine in its pursuit of justice amid Russia’s ongoing war, as well as on how international law must evolve to respond to modern forms of aggression and propaganda.

Herbert R. Reginbogin explained that he began work on the book together with his co-author, Marshall J. Breger, shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as scholars sought to reinterpret the Nuremberg Principles in light of new realities. He noted that the original Nuremberg Trials were not only about punishing Nazi crimes but also about creating a new legal order based on the accountability of state leaders.

“Even a president or a king can be held responsible. Nuremberg was about law: if there is no law, there is no crime,” he said. He added that the U.S. prosecutor at Nuremberg introduced the idea of natural law, emphasizing that no authority can deprive a person of their inalienable rights and dignity — “even someone in custody must be treated as a human being.”

Professor Reginbogin also highlighted the role of evidence in modern justice, noting that verified digital materials are fully legitimate under international law: “If a document is original and authenticated, it is one hundred percent evidence.”

Anton Korynevych shared that contributing to the book was both an honor and a professional duty for him. “Nuremberg was the first legal process against aggressors after the Second World War. The principles established there shaped modern international law.” He recalled that Raphael Lemkin, the author of the Genocide Convention, was frustrated that the definition of genocide was limited to national, ethnic, racial, and religious groups, excluding political and cultural destruction.

Oleksandra Romantsova emphasized the lack of accountability for contemporary propaganda crimes, noting: “Now we are working with something new — the work of propagandists. Is it possible to view freedom of speech in the context of international crimes, and how can we address this type of offense? We can clearly see how the voices of Russian propagandists influence the war. Is it possible to witness a change in these principles in this regard?”

In response, Anton Korynevych underscored the urgent need for Ukrainians to recognize the longstanding threat posed by Russia: “It is very important for Ukrainians to understand that Russia has sought to destroy us for centuries; they believe we are not real. It takes centuries to erase our culture. The Russian regime has never been brought to justice. I believe that we are now beyond the red line. If Russia does not face justice this time, then can we even speak of law at all? These processes — including those of the International Criminal Court and the special tribunal — represent a crucial moment when we must hold Russia accountable.”

Mr. Korynevych further added that addressing propaganda crimes could be effective within the ratione materiae (subject-matter) jurisdiction of a special tribunal: “There is direct and public incitement to genocide. National and international courts must work to bring perpetrators to justice and address crimes of legal propaganda and related acts. They have vast possibilities to work with these offenses.”

Oleksandra Romantsova also raised questions about preserving the Nuremberg legacy in the twenty-first century and adapting it to new threats, such as state-sponsored propaganda and the militarization of education in Russia. “Can incitement and propaganda that fuel aggression be treated as international crimes?” she asked. She also noted the absence of accountability for Stalinist crimes and emphasized that international law still struggles to fully respond to ideological violence.

Professor Herbert Reginbogin stated that understanding international customary law is key: “International law develops through norms and state practice. Precedents define what types of crimes become admissible. Education is also part of that narrative — when we write schoolbooks, we must ask difficult questions. It’s about freedom of speech and responsibility. It is important to recognize that you live in a new world: never before has a country sought justice for crimes while simultaneously fighting a war on its own territory.”

The speakers also discussed the crucial role of civil society and journalists in ensuring justice. Professor Reginbogin noted: “You are the ones running democracy, and you must understand your mission — that is how public opinion is shaped. That is how accountability begins.” Anton Korynevych also acknowledged the active role of Ukrainian civil society: “The results we have achieved since 2014 would have been impossible without activists, NGOs, and journalists. It doesn’t matter where we sit — what matters is what we think. We all have one common enemy — Russia.”

When asked from the audience about evidence of genocide in Ukraine, Mr. Korynevych highlighted the legal and procedural challenges: “Whenever you start a legal process, you must ensure it can lead to success. You cannot begin a case that you do not believe will succeed. We must prove mens rea — the intent — not just actus reus — the criminal act itself. That is why Ukrainian courts must continue issuing public judgments against propagandists. These will become the foundation for further international action. Without national verdicts, it is difficult to move cases to international courts. The International Court of Justice should be the last resort, once all other layers of accountability have been exhausted.”

Herbert R. Reginbogin concluded the discussion with a powerful remark: “It is very difficult to prove genocide in court. The Holocaust is an example — it was proven because there was overwhelming evidence. If it is not possible to fully prove genocide, we must turn to other crimes — for instance, crimes against humanity — which have been consistently proven in courts. The key is to pursue justice that is both realistic and enforceable.”

The discussion concluded that Ukraine cannot wait passively for “its own Nuremberg.” Justice must begin now — through documentation, public awareness, and international cooperation. The Nuremberg legacy, the speakers agreed, is not only about the past but also about shaping the moral and legal foundations for Ukraine’s future peace.

Author: Olesia Leleka, volunteer at the Center for Civil Liberties.

This event is funded by the European Union. Its contents are those of the Center for Civil Liberties and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.