Ukraine’s Government Proposes to Ban Import of ‘anti-Ukrainian’ Books from Russia

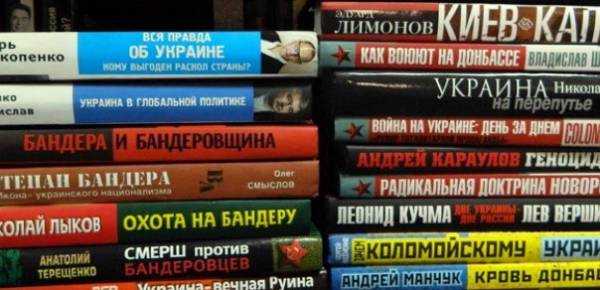

Photo: Centre for Information on Human Rights

Ukraine’s Cabinet of Ministers has tabled a draft law proposing that books imported from Russia be checked for any ‘anti-Ukrainian’ content. Similar measures earlier targeted specific books and elicited protest. The new draft bill seems more sweeping in its potential scope, and dangerously vague.

The draft bill proposing ‘to restrict access to the Ukrainian market of foreign printed material with anti-Ukrainian content’ was adopted by the Cabinet of Ministers on September 8. Deputy Prime Minister Viacheslav Kyrylenko has since said that he is confident the law will be passed before the end of the year, and has called such a ban an important step for Ukraine’s “humanitarian security”.

The bill would effectively impose a permit system for printed material from an aggressor state. At present, only one country has been identified as such, namely the Russian Federations. Kyrylenko asserts that the bill has been discussed with publishers and agreed with key ministries and departments.

Amendments are proposed to three laws relating to the publication of printed material. Many of the prohibitions on, for example, calls to violently change Ukraine’s constitutional order or propaganda of violence are already present in Ukrainian legislation.

What seems entirely new, and woolly, is the following:

“popularization or propaganda of bodies of an aggressor state and their particular actions which create a positive image of the employees of the aggressor state, employees of Soviet State Security bodies, justify or declare as legitimate occupation of Ukrainian territory”.

Would this mean that import would be banned of Russian books, journals and newspapers which treated Crimea under Russian occupation as ‘Russian’? Or, of publications painting a Russian official in a positive light when their actions have nothing to do with Ukraine at all?

This seems unlikely, yet who would determine which publications were excessive, which not? There is scope for corruption in any law which might or might not be applied.

An ‘expert council’ is mentioned as responsible for assessing material. How such a council would be formed, and what criteria would be applied need to be clearly defined.

The bill, its authors stress, applies only to import. There would be no ban on bringing in up to 10 copies of a publication.

Russian propaganda and, often, warmongering, reached dangerous proportions with Russia’s invasion of Crimea and military intervention in Eastern Ukraine. Measures are undoubtedly needed to counter the lies told, especially in areas within or close to territory under Russian occupation or Kremlin-backed militant control.

It is not clear that this law, nor previous legislative initiatives achieve that aim, while being guaranteed to elicit accusations that Ukraine is introducing censorship.

In August 2015 Ukraine’s Fiscal Service barred 38 Russian books from being imported into Ukraine. The ban was imposed “in order to prevent Ukrainian citizens being subjected to methods of information war and disinformation, the spreading of people-hating ideology, fascism, xenophobia and separatism, as well as to stop encroachments on Ukraine’s territorial integrity and constitutional system”.

The list included works by fascist ideologist Alexander Dugin, founder of the National Bolshevik Party and now leader of the Other Russia party Edward Limonov; Sergei Glazyev, senior advisor to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Among the books banned is Valery Korovin’s “End of the Ukraine Project”.

The role directly played by Glazyev in stirring up (or trying to instigate) unrest in Donbas, Kharkiv, Odesa and Zaporizhya was effectively confirmed in August this year when Ukraine’s Prosecutor General’s Office released what appear to be recordings of intercepted telephone conversations.

The material is incriminating but revealed little that was genuinely new. His role and that of the others whose books were banned had long been known.

Dugin and Limonov and their organizations provided active support and training to militants in Donbas, as well as a considerable number of fighters, from the outset.

The problem, of course, was that the specific books were only part of a huge output from the individuals in question. Their ban only gave them unwarranted publicity, making it much more likely that people would suddenly decide to download them from the Internet, without any bans.

Kyrylenko noted that at a book fair in Kyiv in May this year, books by Dugin were on sale, having been imported legally into the country.

The main absurdity of last year’s ban lay in the fact that one of the main sources of false and distorted information from Russia about Ukraine comes from the Russian Foreign Ministry, and that cannot be banned. That has not changed. In a Bloomberg interview, Russian President Vladimir Putin repeated Russian propaganda’s most toxic lies about the Odesa May 2, 2014 tragedy. He was not challenged at the time, nor later.

Such bans can be a propaganda coup to Russia which makes much of any such ‘restriction of Russian readers’ rights’ in Ukraine while conveniently muffling its own strict censorship. With the media mostly under state control in Russia, and independent sites blocked, it has little problem in doing so.

by Halya Coynash for http://khpg.org