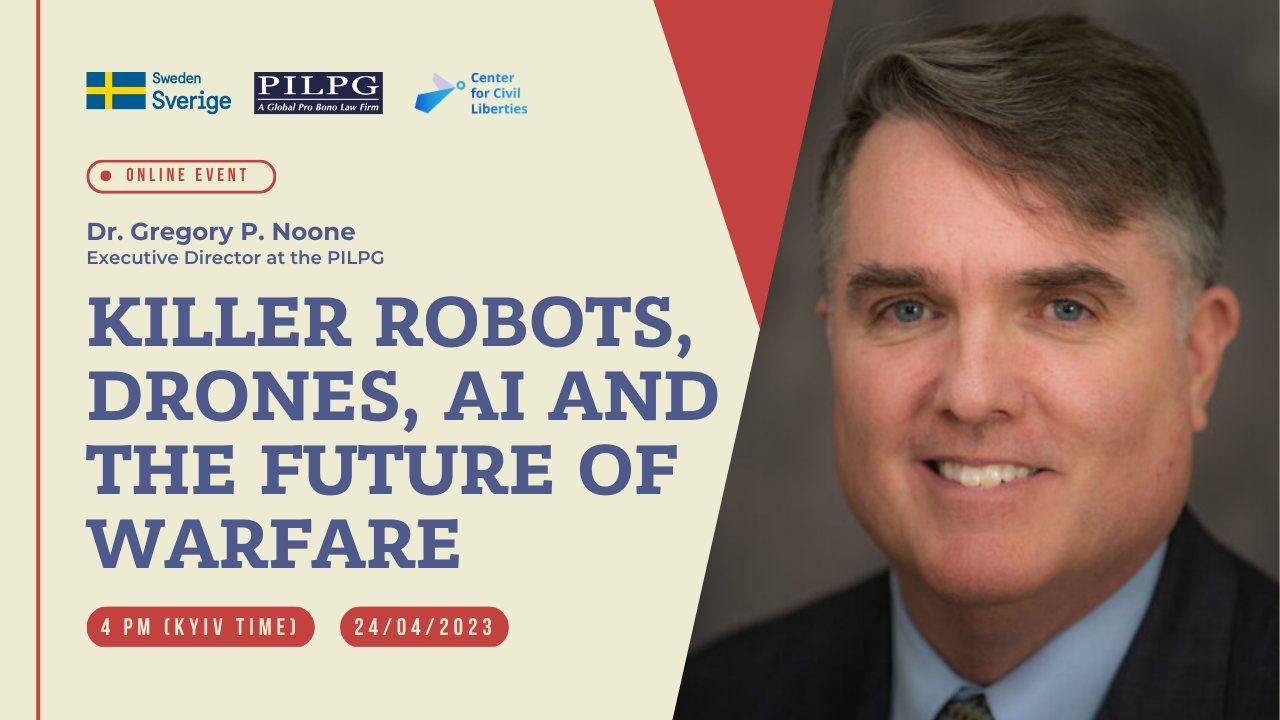

Killer robots, drones, AI and the future of warfare

Center for Civil Liberties and Public International Law & Policy Group conducts a series of public lectures dedicated to IHL/LOAC (International humanitarian law/Law of Armed Conflict) studies.

The idea to conduct IHL training sessions to Ukrainian civil society originated from CCL efforts in documenting war crimes committed by Russia and its proxies. In this regard PILPG expertise and experience in this field are of great help.

Since 2022 PILPG, a Nobel Peace Prize nominee, is working in Ukraine on documentation and transitional justice.

The US military has updated its Department of Defense directive to focus on the use of autonomous weapons, marking its first revision in a decade. The development follows the announcement by NATO in October 2022 of an implementation plan designed to maintain the alliance’s technological lead. The increasing use of semi-autonomous missiles in Ukraine is creating pressure to use fully autonomous weapons on the battlefield. However, critics, including the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, argue that autonomous weapons lack the judgment required to distinguish between civilians and legitimate military targets, and that the risk of weapons being used by terrorists and other non-state actors is too high.

For some time Lethal autonomous weapons have now been used on the battlefield. Ukraine is no exception. Both sides use drones for reconnaissance and conduct of hostilities.

On Monday the 24 of April 2023, our lecturer Dr. Gregory P. Noone examine various aspects of LAWs in his second lecture for CCL including:

– the key issues raised by autonomous weapon systems under international humanitarian law (IHL);

– legal terminology, definition surrounding LAWs;

– what are the ethical concerns of killer robots?

– are lethal autonomous weapons unethical?

– are killer robots banned?

– what weapons are classified under the definition of Lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS)?

– did the UN fail to agree on the killer robot ban?

– which countries are against the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots?

– are existing international humanitarian law is sufficient enough regulation for this area?

– what is the law of robotic warfare?

– and how all of this concerns Ukraine now.

Dr. Gregory P. Noone put IHL norms into the present 2022-2023 Russia aggression. The lecture was followed by a conversation with Dr. Gregory P. Noone and a questions and answer session moderated by CCL coordinator Mr. Roman Nekoliak.

The event page on Facebook and LinkedIn

To follow up the discussion watch a video recording.

Speaker: Dr. Gregory P. Noone.

Dr. Gregory P. Noone, Ph.D., J.D., is an Executive Director at the Public International Law and Policy Group (PILPG). Dr. Noone works on PILPG’s Ukraine and Yemen projects related to peacebuilding, transitional justice, and human rights documentation. Dr. Noone has conducted PILPG justice system assessments in Uganda and Côte d’Ivoire as well as provided transitional justice assistance in post-Gaddafi Libya and to the Syrian opposition. Dr. Noone was also part of the international effort investigating the Myanmar government’s atrocities committed against the Rohingya population. He worked as an investigator in the refugee camps in Bangladesh and as one of the legal experts on the report’s findings.

He has published and presented articles on the Rwandan Genocide, the Law of Armed Conflict, the International Criminal Court, and Military Tribunals at numerous forums. Dr. Noone is the co-author (with Laurie R. Blank) of the widely used textbook: International Law and Armed Conflict: Fundamental Principles and Contemporary Challenges in the Law of War Second Edition (Aspen / Wolters Kluwer Publishing 2019). Together they also published the Concise Edition of this textbook (Aspen / Wolters Kluwer Publishing 2016) for use in military academies, war colleges, undergraduate universities, and for foreign militaries. Dr. Noone is also the co-author (with Laurie R. Blank) of the Law of War Training: Resources for Military and Civilian Leaders derived from a multi-year project on military training programs in the law of war. Dr. Noone appears regularly as a commentator on international and national TV and radio.

Target audience

– Researchers and advanced students (master’s or PhD) in the fields of human rights and IHL, international law, political science, philosophy, or computer science

– Policy analysts and legal advisers working on innovation and technology in public or private institutions, military

– Industry professionals working the law and governance of AI

The development of these seminars has been made possible through the support of the Public International Law & Policy Group.

Pupils expectations:

– “I am curious to expand my knowledge on this topic, especially within IHL and the current Russian war against Ukraine perspective”.

– “I have been attending webinars like this sponsored by The Washington Post, however, this talk seems especially in-depth and pertinent to the current events in Ukraine”.

– “Learn new things about the impact of new technologies on the methods of waging war (including the war in Ukraine), on international humanitarian law, transitional justice”.

– “I am interested in current problems of international humanitarian and international criminal law”.

– “I am in particular interested in Warfare technology, how it is developing, and especially how this pertains to the present and future of Ukraine and NATO”.

Main takeaways:

Fully autonomous weapons, also known as “killer robots,” raise serious moral and legal concerns because they would possess the ability to select and engage their targets without meaningful human control. They are also known as killer robots or lethal autonomous weapons systems. Because of their full autonomy, they would have no “human in the loop” to direct their use of force and thus would represent the step beyond current remote-controlled drones.

There are also grave doubts that fully autonomous weapons would ever be able to replicate human judgment and comply with the legal requirement to distinguish civilian from military targets.

IHL is more than just humanitarian aspects. It is a balance between humanity and military necessity.

LAWS will become a crucial factor on the battlefield of the future.

Note: LAWS (killer robots) are one step further from drones.

→ There are potential humanitarian and military benefits of the technology behind LAWS, so it is premature to ban them.

Arguments:

o IHL provides an adequate system of regulation for weapon use.

o The Law of war requires that individual human beings ensure compliance with the principles of distinction and proportionality, even when using autonomous weapon systems.

o States are responsible for the use of weapons with autonomous functions through the individuals in their armed forces, and that they can use investigations, individual criminal liability, civil liability, and internal disciplinary measures to ensure accountability. (+ art. 28 Rome Statute)

o Commanders currently authorize the use of lethal force, based on indicia like the commander’s understanding of the tactical situation, the weapon’s system performance, and the employment of tactics, techniques and procedures for that weapon. Understanding that states will not develop and field weapons they cannot control, the U.S. urged a focus on “appropriate levels of human judgment over the use of force,” rather than the controllability of the weapon system.

o Advances in autonomy could facilitate and enhance the implementation of IHL—particularly the issues of distinction and proportionality. Autonomy-related technologies might enhance civilian protection during armed conflict in five ways:

o Electronic self-destruction mechanisms and electronic self-deactivating features that can help avoid indiscriminate area effects and unintended harm to civilians or civilian objects.

o Artificial intelligence (AI) could help commanders increase their awareness of the presence of civilians, civilian objects and objects under special protection on the battlefield, clearing the “fog of war” that sometimes causes commanders to misidentify civilians as combatants or be unaware of the presence of civilians in or near a military objective.

o AI could improve the process of assessing the likely effects of weapon systems, with a view toward minimizing collateral damage.

o Automated target identification, tracking, selection and engagement functions can reduce the risk weapons pose to civilians, and allow weapons to strike military objectives more accurately.

o Emerging technologies could reduce the risk to civilians when military forces are in contact with the enemy and applying immediate use of force in self-defence.

→ Legal and moral dilemmas arising as a result of changes in the contemporary security environment in relation to LAWS:

- Legal: The existing legal framework is ill-suited and inadequate

- Moral: LAWS is capable of taking targeting decisions independently of human involvement

Legal Framework (IHL)

oAP1 Article 36 “In the study, development, acquisition or adoption of a new weapon, means or method of warfare, a High Contracting Party is under an obligation to determine whether its employment would, in some or all circumstances, be prohibited by (…) international law.”

o Obligation to conduct a legal review of new weapons applies both in times of armed conflict and in times of peace. In other words, whether the weapon is capable of being used in compliance with IHL.

o The legal assessment should take into account the combination of design and manner in which it is used (design & characteristics + when and where it is intended to be used)

o Aim: the weapons should be developed, manufactured or procured by States in compliance with international law. More specifically, the purpose of the review is to prevent the use of weapons that would always violate international law and to restrict the use of those that would violate

international law and to restrict the use of those that would violate international law in some circumstances.

o Applies to all States irrespective of their treaty obligation.

The doctrine of command responsibility

The doctrine of command or superior responsibility stipulates that a superior—a military or civilian leader—can be held criminally responsible when his subordinates commit international crimes. The doctrine has become part of customary international law and has been incorporated into the statutes of the international criminal tribunals and into the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC). The superior incurs criminal responsibility for failing to have prevented (or repressed) criminal acts committed by his subordinates.

Legal analysis (ICRC)

o The possibilities provided by and interpretation of the current legal framework

- Existing mechanisms for legal accountability are ill-suited and inadequate to address the unlawful harms fully autonomous weapons might cause

o Gaps in the current legal framework (as ICRC contra LAWS) - Neither criminal law nor civil law guarantees adequate accountability for individuals directly or indirectly involved in the use of fully autonomous weapons (existing mechanisms for legal accountability are ill suited and inadequate to address the unlawful harms fully autonomous weapons might cause).

- Fully autonomous weapon itself could not be found accountable for criminal acts that it might commit because it would lack intentionality. In addition, such a robot would not fall within the “natural person” jurisdiction of international courts.

- They would lack human characteristics generally required to adhere during armed conflict to foundational rules of international humanitarian law, such as the rules of distinction and proportionality.

- Robot could neither be deterred by condemnation nor perceive or appreciate being “punished”

- Human commanders or operators could not be assigned direct responsibility for the wrongful actions of a fully autonomous weapon, except in rare circumstances when those people could be shown to have possessed the specific intention and capability to commit criminal acts through the misuse of fully autonomous weapons

- It would be unreasonable to impose criminal punishment on the programmer or manufacturer, who might not specifically intend, or even foresee, the robot’s commission of wrongful acts. Moreover, a plaintiff would find it challenging to establish that a fully autonomous weapon was legally defective for the purposes of a product liability suit. (In addition, most victims would find suing a user or manufacturer difficult because their lawsuits would likely be expensive, time consuming, and dependent on the assistance of experts who could deal with the complex legal and technical issues implicated by the use of fully autonomous weapons.)

It could trigger the doctrine of indirect responsibility, or command responsibility. A commander would nevertheless still escape liability in most cases. Command responsibility holds superiors accountable only if they knew or should have known of a subordinate’s criminal act and failed to prevent or punish it. These criteria set a high bar for accountability for the actions of a fully autonomous weapon.

Note also: moral perspective

- Many people find objectionable the idea of delegating to machines the power to make life-and-death determinations in armed conflict or law enforcement situations

- Although fully autonomous weapons would not be swayed by fear or anger, they would lack compassion, a key safeguard against the killing of civilians

- The use of robots could make it easier for political leaders to resort to force because usingsuch robots would lower the risk to their own soldiers

- Could also trigger an arms race

- “Recipe for impunity”?

- (Source: Mind the Gap: The Lack of Accountability for Killer Robots)

Public International Law & Policy Group is a global pro bono law firm specializing in peace negotiations, post-conflict constitutions, and transitional justice. The PILPG operates as a non-profit, global pro bono law firm providing free legal assistance to its clients, which include governments, sub-state entities, and civil society groups worldwide.

PILPG provides pro bono legal counsel to clients on peace negotiation, drafting of post-conflict constitutions, creation and operation of transitional justice mechanisms, and ways to strengthen the rule of law and effective institutions.

Since 1995, they have worked with over 40 state and non-state parties and provided legal assistance to all major war crimes tribunals. The organization was founded in London in 1995, and is currently headquartered in Washington, DC.

With over 700 alumni, PILPG continues to train and empower the next generation of peace-builders and public international lawyers.