The Issue of Illegally Detained Persons Release Within the Limits of the Armed Conflict between Ukraine and the Russian Federation: How to Overcome the Deadlock

Issue background

The military occupation of Crimea by the Russian Federation and the ongoing hybrid war in Donbas have resulted in numerous human rights violations and the emergence of new categories of victims in the ongoing armed conflict.

In Crimea, the occupational authorities began to launch trumped-up criminal cases under the articles of “sabotage”, “participation in a terrorist organization”, “espionage”, “calls for destructing the territorial integrity”, etc. against people who began non-violent resistance or publicly spoke out in defense of rights and freedoms.

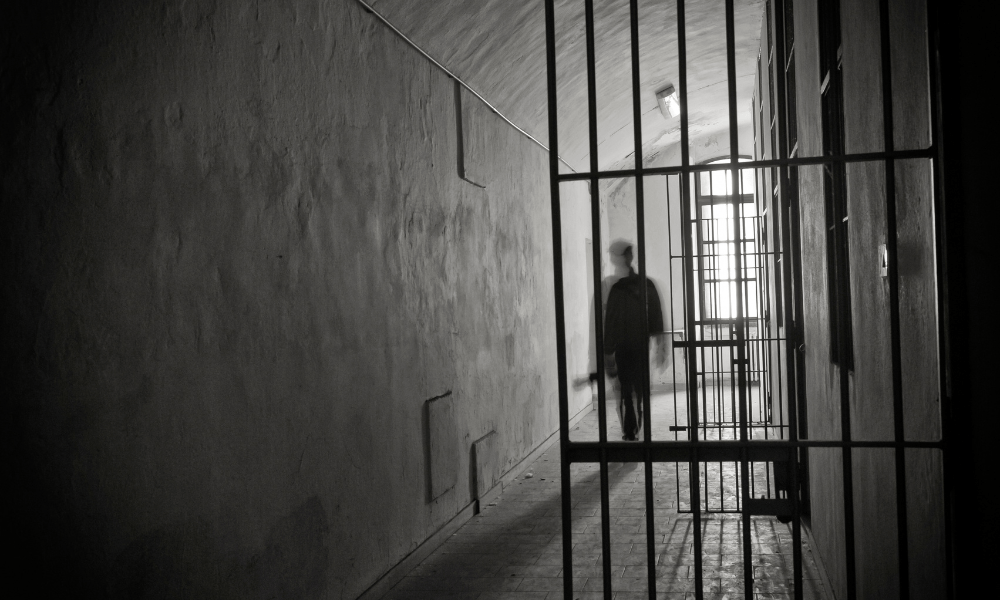

In the occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk regions, people who supported or were suspected of supporting the territorial integrity of Ukraine were subjected to enforced disappearance, extrajudicial executions, torture and illegal detention in an extensive network of so-called official and secret places of detention, most of them are not suitable even for the temporary stay of prisoners.

At the same time, in the Russian Federation itself, similar cases were framed up against the citizens of Ukraine, who were just in the wrong place at the wrong time, and, from the media point of view, were attractive for maintaining the “enemy image”.

A striking example is the case of Serhii Lytvynov, a resident of the village of Komyshne in the Luhansk region, who was arrested in the Russian Federation on an absurd charge. He allegedly killed and raped several dozen women in the Luhansk region by order of the then head of the Dnipropetrovsk regional state administration “with the aim of genocide of the Russian-speaking population of Donbas.” After working off the information picture on the Russian television necessary for military propaganda, the investigation reached the dead end. Despite the fact that Serhii Lytvynov himself admitted his guilt, it turned out in court that neither the women indicated in the case materials, nor the addresses of the houses where his crimes were allegedly committed, in reality did not exist. Therefore, the Russian law enforcement agencies were forced to initiate a new criminal case on a different corpus delicti, according to which, in the end, Serhii Lytvynov was imprisoned.

The ongoing hostilities in Donbas have led to the capture of representatives of the Armed Forces of Ukraine and the Armed Forces of Russia, as well as representatives of illegal military groups who had Russian citizenship controlled by the Russian Federation, which, in accordance with the Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War and the Additional Protocol to it, were obliged to receive the appropriate legal status, a number of guarantees in accordance with international humanitarian law, as well as the immunity of a combatant related to participation in armed conflicts, but does not apply to their commission of war crimes. The vast majority of these guarantees were not respected by the Russian Federation, exercising the effective control over the so-called Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics. Ukraine that announced an “anti-terrorist operation” in the eastern territories of the country, and later replaced it with the “joint forces operation”, during these years also did not determine the legal status of prisoners of war to these categories of people [1].

In addition, in contrast to the combatants held on the territory of Ukraine from the territory of Donetsk and Luhansk regions, people under the de facto control of the Russian Federation did not allow representatives of international organizations, including the International Committee of the Red Cross to access the prisoners of war, which was one of the reasons of the widespread practice of torture, cruel treatment, and murder, as well as failure to provide medical aid to Ukrainian prisoners of war, recorded by the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights according to the testimony of those freed.

Despite the fact that the Russian Federation consistently refuses to be a party to the armed conflict in accordance with the annual report on preliminary investigations of the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court in the context of considering the situation in Ukraine, made the following conclusions, “According to the information, the situation in Crimea and Sevastopol is tantamount to the international armed conflict between Ukraine and the Russian Federation. This international armed conflict began no later than February 26, when the Russian Federation used its armed forces to gain control over parts of Ukraine’s territory without the consent of the Ukrainian government. The law of international armed conflicts is also applicable after March 18, 2014, to the extent that the situation on the territory of Crimea and in Sevastopol will be tantamount to the ongoing occupation”.

Regarding the situation in Donbas, the International Criminal Court tentatively established the following: “According to available information, until 30 April 2014, the tension of hostilities between the Ukrainian government forces and anti-government armed elements in eastern Ukraine had reached a level that would entail the application of the law of armed conflict. Moreover, according to available data, the level of organization of armed groups operating in eastern Ukraine, including the LPR and DPR, at that time reached the level sufficient to consider these groups the parties to the non-international armed conflict. Additional information, for example, reports of shelling of enemy military bases by both states, as well as arrests of Russian military personnel by Ukraine and vice versa, indicate a direct military confrontation between the Russian armed forces and the forces of the Ukrainian government, which presupposes the existence of the international armed conflict in the context of hostilities in the east of Ukraine at the latest from 14 July 2014 simultaneously with the existence of the non-international armed conflict.”

Why does the Kremlin need illegal prisoners?

Currently, according to the Center for Civil Liberties, at least 127 people are imprisoned for political reasons in occupied Crimea and the Russian Federation, 89 of them are Crimean Tatars. About 300 people are held in the status of prisoners of war and civil hostages on the territory of part of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, which are under the de facto control of the Russian Federation, according to the official data of the Security Service of Ukraine. But these figures are only the tip of the iceberg, a real number of people imprisoned due to the armed conflict in these territories is unknown.

This situation has not only a humanitarian dimension, but also a geopolitical one. The Russian Federation uses illegally imprisoned people to achieve various goals: Russian journalism spins invented accusations in order to increase the readiness of the Russian population for war; in political negotiations, the Kremlin in exchange for the release of people requires Ukraine to make specific political decisions, and finally, the Russian Federation, in various conflicts, uses the practices of destroying an active minority as a method of waging war and maintaining the occupied territories.

Hostages as warfare practices

In the first months of the war, illegal armed groups controlled by the Russian Federation began a deliberate policy of terror against the civilian population. Their task was to squeeze out or physically destroy the active minority and intimidate the majority in order to quickly gain control over the region. That is why, in addition to the so-called official, an extensive network of secret places of detention was created, where people were kept incommunicado without any connection with the external world. After the Russian Federation officially recognized its jurisdiction over the occupied peninsula, such secret places created by the so-called Crimean Self-Defense gradually ceased to function, but in the occupied territories, parts of the Luhansk and Donetsk regions continue to work. In particular, the infamous “Isolation” secret prison, located on the territory of the military base in Donetsk, despite its secrecy, is mentioned in every periodic report of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and has long become a symbol of terror.

In the course of documenting the testimony of people released from captivity, human rights organizations identified about a dozen citizens of the Russian Federation as organizers and direct perpetrators of these war crimes in Crimea and Donbas, and before that in Transnistria, Chechnya, Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

The Russian Federation successfully using the technology of armed conflict with a deliberate policy of committing war crimes against civilians to achieve geopolitical goals. All identified individuals have never been punished for their crimes in previous armed conflicts, which encourages the continued use of this warfare method in new gray zones.

Hostages as the way to form the image of the enemy

The lists of prisoners for political reasons include people of two conventional categories. The first includes those who were sent to jail because of their non-violent public activities. A striking example is the case of Crimean Tatar Emir-Usein Kook. After the occupation of Crimea, he began human rights work in the new Crimean Contact Group on Human Rights, consulted the relatives of the missing people and victims of political persecution. After several warnings and preventive conversations near his own house, he was abducted and beaten by unknown persons. Although later it turned out that these were FSB officers, a criminal case was launched against Emir-Usein. At first, he was charged with extremism for an old post on social networks. And only later he was formally charged with participation in a terrorist organization and was sentenced in the trumped-up criminal case to 12 years in prison.

At the same time, many people on the lists did not carry out any public activities in defense of rights and freedoms. For example, Yuriy Soloshenko (now deceased), the former director of the plant and the pensioner, who left for Moscow at the invitation of his former acquaintance, allegedly for a consultation. He was arrested upon arrival on trumped-up espionage charges and sentenced to six years in prison.

The fact is that television plays an important role in the war that the Russian Federation has started against Ukraine. That is why it is necessary to periodically show Ukrainian spies, punishers, terrorists representing the “fascists who seized power in Kyiv” and “crucified the boy in Sloviansk,” and also rushed to Russia to blow up schools and prepare terrorist attacks.

The so-called Russian journalism turned into the mass-media division of the military industrial system of the Russian Federation long ago. The objective of these often absurd fictional cases is to form the image of enemy out of Ukrainians and to make the Russian population to hate them. Therefore, there are such fantastic versions of the accusation, according to which Mykola Karpiuk and Stanislav Klykh, arrested in the Russian Federation, together with ex-Prime Minister of Ukraine Arsenii Yatseniuk, lying on their stomachs on Minutka Square, shot the Russian military in Chechnya. The name of Arsenii Yatseniuk was mentioned 228 times in the indictment. And it would be ridiculous if there were no several years of real imprisonment, tortures by hunger, electric shock and physical pain, after which Stanislav Klych undermined his mental health. And when Arsenii Yatseniuk was detained at the Geneva airport in December 2017 at the request of Russia in Interpol in this case, there was nothing to laugh about.

Hostages as the resource for achieving political objectives

For people who follow domestic politics in Russia, it is obvious that for the established in the Russian Federation regime, not only the lives of Ukrainian citizens, but also their own ones, are of no value. That is why, in spite of the bravado like “Russians don’t leave their own behind,” no one is particularly interested in the fate of Russian “volunteers” in Ukrainian prisons. Political demands were put forward during all the negotiations, where the issues of releasing the Kremlin hostages were raised. It is quite easy to track it down, even at the level of dry statements made by Kremlin speakers based on the results of their meetings over the years.

The Kremlin has never been interested in people fighting in Ukraine on its orders. The Kremlin has been interested in amendments to the Constitution of Ukraine, the holding of elections in the east of the country, a total amnesty for war criminals, the restoration of water supply to the occupied Crimea. So, in September 2019, Ukraine was forced to release Volodymyr Tsemakh, the defendant in the case of the shooting down the Malaysian Boeing, and in December 2019 – 5 Berkut soldiers, whose trial in the case of the murder of 48 Maidan participants in Instytutska Street was coming to an end.

Blackmailing and using hostages to achieve political goals is also quite successful, given the sensitivity of the topic of hostages in the Ukrainian society. Tired of waiting and annoyed with explanations like “Putin has all keys”, the prisoners’ relatives cannot reach the leaders of the Russian Federation. Instead, they transfer their anger to the Ukrainian authorities, who could really be blamed in this situation (for example, the delay in resolving the issue of medical and social support at the legislative level or the President of Ukraine’s long-term non-signing of law No. 2689 on war criminals), but definitely not that they can easily solve this problem when this situation is outside the legal environment. No wonder, on October 14, 2019, political prisoner Oleksandr Shumkov began a hunger strike. One of his demands was that Russia should stop using Ukrainian political prisoners to put pressure on Ukraine in the Minsk and Normandy formats and to withdraw troops in Donbas.

Obstacles standing in the way of the Minsk Protocol implementation

Back in February 2015, during the signing of the Minsk Protocol, paragraph 6 was included in the text signed by the representative of the Russian Federation. According to it, the parties were obliged to “Ensure the release and exchange of all hostages and illegally detained persons, based on the principle of “all for all”. This process must be completed no later than the fifth day after the pull-out of troops.”

In fact, this release process has never been completed. Moreover, every month, new cases of enforced disappearances and illegal imprisonment of civilians were recorded in the occupied territories. For example, the last high-profile arrests in Crimea were registered immediately after the founding summit of the Crimean Platform in September 2021, when Nariman Dzhelal, the first deputy chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, was accused of sabotage among the detained Crimean Tatars.

The process of exchange within the framework of the Minsk talks reached the dead end. The last exchanges took place back in 2019. Thus, in September 2019, Ukrainian director Oleg Sentsov returned to Ukraine together with 34 other people who were imprisoned for political reasons in Russia and occupied Crimea. In December 2019, the authorities managed to release 76 people who were illegally imprisoned in the occupied Donbas. After these exchanges and as of mid-November 2021, there was no progress in the release of illegally detained people.

The practice of liberation immediately laid systemic problems when chaotic exchanges, redemption of captives or voluntary release of soldiers at the request of mothers by the leaders of illegal armed groups were transferred to centralized exchange under the control of the Russian Federation.

First, instead of the concept of the simultaneous liberation of all for all, the practice of exchange was introduced. But exchange is an economic category that immediately aroused the demand and the need for a constant increase in the amount of the “exchange fund”, the appearance of “1 to 2” ratios and others as conditions for the release of people from the lists.

Second, it is still not clear how to solve the issue with the lists of prisoners. The official list of illegally imprisoned people from the Ukrainian part is classified, and it is simply impossible for human rights defenders and relatives to verify who and on what grounds was included there. The lack of information about the situation in the “gray zone”, which has become the territory of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions under the control of the Russian Federation, also affects. There are instances when some people after their release seek help from human rights organizations, and only after that, state bodies will find out about the fact of their illegal detention. It is easy to assume that many detentions generally go without the attention of the relevant structures, since relatives in the occupied territories for various reasons may not apply to the official government bodies.

In addition, the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics do not recognize relation to the armed conflict arrests of some people included in the official lists by the Ukrainian part. According to their position, these people violated the laws of the republics, and therefore they are ordinary criminals and are not subject to the terms of the Minsk Protocol.

Third, the principle of “all for all” has de facto become “all established for all established.” There was often a situation when representatives of the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk republics, which are de facto under control of the Russian Federation, denied the fact of the arrest and detention of the mentioned person during the meetings of the humanitarian subgroup in Minsk. The fact that the relatives had in the official answers of the occupation authorities indicating the charge brought and the actual location did not change the situation. They took time to verify the information, and such verification could last for years without changes.

The example is the detention of Andrii Harrius from the settlement of Krynychna in Makiivka. He was detained in front of his pregnant wife and little son in December 2018. The relatives received official letters from the so-called General Prosecutor’s Office of the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Ombudsman of the Donetsk People’s Republic about the chosen pre-trial restrictions and the place of detention of their son. At the same time, during the negotiations in Minsk, the Ukrainian subgroup was informed that the mentioned person was not detained, and his whereabouts are unknown to the authorities of the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic.

Fourth, the Russian Federation put forward political demands for the Ukrainian authorities to make certain steps as conditions for the exchange: amendments to the Constitution, elections in the east of the country, total amnesty for war criminals, restoration of water supply to occupied Crimea, etc. This line could be traced even through public statements by officials of the Russian Federation on the results of the negotiations.

And finally, despite the fact that people imprisoned for political reasons in occupied Crimea are also victims of the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian armed conflict, the Russian Federation has consistently refused to discuss the release of these people, arguing that they are located and allegedly committed crimes in the territory of the Russian Federation.

The situation is complicated by the serious chronic diseases or health problems as a result of tortures and inhuman conditions of detention for a number of illegally detained people in ORDLO (temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine), which was aggravated by the risks due to the pandemic and the lack of proper medical care. Such people may simply not live to see the next round of release.

The case of doctor Natalia Statsenko, who was detained in July 2019 on trumped-up charges of espionage, can serve as the example. For the past six years, Natalia has had problems with her back. Right before her arrest, she was diagnosed with vertebrae collapse and underwent emergency surgery. Her health rapidly deteriorated, in addition to all, she began to suffer from hypertensive crisis. She does not receive any medical care, which, according to his father, has already led to partial paralysis of one limb. The trial of Natalia is still going on. At the preliminary court hearing, Natalia said that she would not live till the next trial.

Instead of conclusions. The need for a new strategy.

At the moment, the Ukrainian authorities and the international community set themselves the goal of releasing all illegally imprisoned people included in the official lists. This turns this task into a constant conveyor, because new cases of enforced disappearances, tyranny, imprisonment based on trumped-up criminal cases and the like take place regularly in the occupied Ukrainian territories. Therefore, by the time of the complete de-occupation of Crimea and the territory of the occupied Donetsk and Luhansk regions, the Ukrainian authorities and the international community must fight for the release of not only those people whose names are on the lists, but also those who will be arrested in the future.

This expression of the goal brings to the foreground the important intermediate tasks for the protection of the rights and freedoms of illegally detained people, strategic changes in the conditions of their detention and their treatment, regardless of the result of reaching agreements on the next exchange. It is important to consolidate efforts to achieve strategic changes in the situation itself, which will help reduce the number of illegally imprisoned in the future and will have a chilling effect on the brutality of human rights violations committed against these people.

Below is the incomplete list of important strategic changes that are required from the Russian Federation and the proxy agents under its control:

1. Free access of the International Committee of the Red Cross to people illegally detained in the territory of the occupied part of Donetsk and Luhansk regions, which is under the de facto control of the Russian Federation. It is important that representatives of this international humanitarian organization be given prompt access to people in places of detention, in full accordance with its mandate and ensuring the principle of confidentiality of such meetings.

2. Closing the secret “Isolation” prison in the territory of the military base and other secret places of detention. It is located in Donetsk in 3 Svitloho Shliakhu St. There are eight cells, two punishment cells and two basement rooms. Mostly civilian hostages suspected of disloyalty are imprisoned there. About 30% of prisoners were women as of October 2019. Known for tortures and ill-treatment of prisoners, regardless of the article, age and state of health. Prisoners are subjected to beating, electric shocks, suffocation (“wet” and “dry” methods), sexual assault, position torture, removal of body parts (nails and teeth), deprivation of water, food, sleep or access to the toilet, imitation of execution, threats of violence or death, threats of harm to the family.

3. Ensuring the basic rights of illegally detained persons in accordance with the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Nelson Mandela Rules) in the territory of the part of Donetsk and Luhansk regions, which is under the de facto control of the Russian Federation. I am referring to the issue granting permission for regular visits with relatives, free transfer of packages with clothes, food and medicine, providing adequate medical care, closing or repairing those cells that do not meet the conditions of detention of people, complete prohibition of torture and inhuman treatment of prisoners, etc.

If we talk about Ukraine, then it must sign draft law 2689 on amending some legislative acts of Ukraine regarding the implementation of the norms of international criminal and humanitarian law. The President of Ukraine has not been signing for more than five months the draft law that amends the Criminal Code of Ukraine and establishes responsibility for crimes against humanity and brings the provisions on war crimes in line with the requirements of international law. And thus it provides the national investigation and the court authorities with the opportunity to effectively prosecute people who have committed basic crimes under international law.

Delaying the adoption of the bill has already led to irreversible consequences. No statute of limitations is applicable only to international crimes, so the correct determination of the nature of these criminal acts today will enable us to bring those responsible to justice in the future, even if it takes decades. Moreover, only those convicted of international crimes will not benefit from the amnesty demanded by Russia under the Minsk process.

The entry into force of this draft law will be a signal to the occupied territories, which could cause a chilling effect on those who commit crimes. History convincingly testifies that circumstances change and authoritarian regimes fall, and those who have committed international crimes will sooner or later be brought to justice. And this understanding that they will not have the opportunity to justify their illegal actions by orders of their leaders can right now save life and health for the illegally detained people in ORDLO (temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine) and occupied Crimea.

[1] Regarding the citizens of Ukraine who have joined illegal armed groups controlled by the Russian Federation, the issue of legal assessment may vary depending on the type of armed conflict.